Recollections of a Lifetime, by Samuel Griswold Goodrich (New York & Auburn: Miller, Orton & Mulligan, 1856); volume 1

[Goodrich’s notes for this volume]

-----

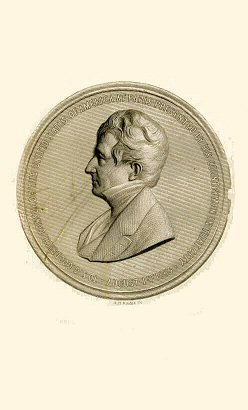

[frontispiece]

-----

[ title page ]

OF

A LIFETIME,

OR

MEN AND THINGS I HAVE SEEN:

IN A SERIES OF

FAMILIAR LETTERS TO A FRIEND,

HISTORICAL, BIOGRAPHICAL, ANECDOTICAL, AND DESCRIPTIVE.

BY S. G. GOODRICH.

VOL. I.

NEW YORK AND AUBURN:

MILLER, ORTON AND MULLIGAN.

New York, 25 Park Row;—Auburn, 107 Genesee-st.

M DCCC LVI.

-----

[copyright page]

Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1856,

By S. G. GOODRICH,

In the Clerk’s Office of the District Court of the United States for the Southern District of New York.

R. C. Valentine,

Stereotyper and Electrotypist,

17 Dutch-st., cor. Fulton,

New York

C. A. ALVORD, Printer,

No. 15 Vandewater Street, N. Y.

-----

[p. 3]

The first Letter in the ensuing pages will inform the reader as to the origin of these volumes, and the leading ideas of the author in writing them. It is necessary to state, however, that although the work was begun two years since—as indicated by the date of the first of these Letters, and while the author was residing abroad—a considerable portion of it has been written within the last year, and since his return to America. This statement is necessary, in order to explain several passages which will be found scattered through its pages.

New York, September, 1856.

-----

[p. 4]

Portrait of the Author … Frontispiece

From the Medallion presented to him by the American citizens in Paris,—on steel, engraved by Ritchie.

Aunt Delight … 36

Making Maple Sugar … 68

Whittling … 94

Catching Pigeons … 100

How are you, Priest? How are you, Democrat? … 130

The Jerking Exercise … 202

Deacon Olmstead … 222

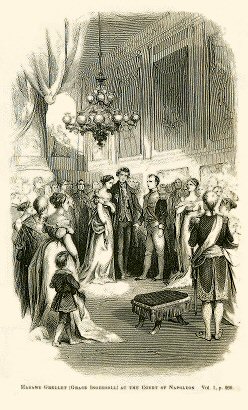

Grace Ingersoll at the Court of Napoleon … 260

The Hermitess … 294

First Adventure upon the sea … 342

The Cold Friday … 394

Peace! Peace! … 505

George Cabot … 36

Emigration in 1817 … 80

Percival … 132

Brainard writing “Fall of Niagara” … 148

Sir Walter Scott, Clerk of the Court of Sessions … 176

Edinburgh … 180

England … 214

Byron’s Coffin … 250

These are God’s Spelling-book … 309

The Student … 433

View in Paris … 502

Rome … 525

-----

[p. 5]

Introductory and Explanatory … 9

Geography and Chronology—The Old Brown House—Grandfathers—Ridgefield—The Meeting-House—Parson Mead—Keeler’s Tavern—Lieutenant Smith—The Cannon-Ball … 15

The first Remembered Event—High Ridge—The Spy-glass—Sea and Mountain—The Peel—The Black Patch in the road … 24

Education in New England—The Burial Ground of the Suicide—West Lane—Old Chichester—The School-House—The First Day at School—Aunt Delight—Lewis Olmstead—A Return after Twenty Years—Peter Parley and Mother Goose … 30

The Joyous Nature of Childhood—Drawbacks—The Small-Pox—The Pest-House—Our House a Hospital—Inoculation—The Force of Early Impressions—Rogers’ Pleasures of Memory—My First Whistle—My Sister’s Recollections of a Sunday Afternoon—The Song of Kalewala— Poetic Character of Early Life—Obligations to make Childhood Happy—Beautiful Instinct of Mothers—Improvements in the Training of Children Suggested—Example of our Saviour—The Family a Divine Institution—Christian Marriage … 41

The Inner Life of Towns—Physical Aspect and Character of Ridgefield—Effects of Cultivation upon Climate—Energetic Character of the First Settlers of Ridgefield—Classes of the People as to Descent—Their Occupations—Newspapers—Position of my Father’s Family—Management of the Farm—Domestic Economy—Mechanical Professions—Beef and Pork—The Thanksgiving Turkey—Bread—Fuel—Flint and Steel—Friction Matches—Prof. Silliman—Pyroligneous Acid—Maple Sugar—Rum—Dram-drinking—Tansey Bitters—Brandy— Whisky—The First “Still”—Wine—Dr. G.’s Sacramental Wine—Domestic Products—Bread and Butter—Linen and Woolen Cloth—Cotton— Flax and Wool—The Little Spinning-wheel—Sally St. John and the Rat-trap— Manufacture of Wool—Molly Gregory and Fuging Tunes—The Tanner and Hatter—The Revolving Shoemaker—Whipping the Cat—Carpets—Coverlids and Quiltings—Village Bees and Raisings—The Meetlng-House that was destroyed by Lightning—Deaconing a Hymn … 56

Domestic Habits of the People—Meals—Servants and Masters—Dress—Amusements—Festivals—Marriages—Funerals—Dancing—Winter Sports—Up and Down—My Two Grandmothers … 83

-----

p. 6

Interest in Mechanical Devices—Agriculture—My Parents Design me for a Carpenter—The Dawn of the Age of Invention—Fulton, &c.—Perpetual Motion—Whittling—Gentlemen—St. Paul, King Alfred, Daniel Webster, &c.—Desire of Improvement, a New England Characteristic—Hunting—The Bow and Arrow—The Fowling-piece—Pigeons— Anecdote of Parson M….—Audubon, and Wilson—The Passenger Pigeon—Sporting Rambles—The Blacksnake and Screech-owl—Fishing—Advantages of Country Life and Country Training … 90

Death of Washington—Jefferson and Democracy—Ridgefield on the Great Thoroughfare between New York and Boston—Jerome Bonaparte and his Young Wife—Oliver Wolcott, Governor Treadwell, and Deacon Olmstead—Inauguration of Jefferson—Jerry Mead and Ensign Keeler—Democracy and Federalism—Charter of Charles II.—Elizur Goodrich, Deacon Bishop, and President Jefferson—Abraham Bishop and “About Enough Democracy” … 106

How People traveled Fifty Years ago—Timothy Pickering—Manners along the Road—Jefferson and Shoe-strings—Mr. Priest and Mr. Democrat—Barbers at Washington—James Madison and the Queue—Winter and Sleighing—Comfortable Meeting-house—The Stove Party and the Anti-Stove Party—The first Chaise built in Ridgefield—The Beginning of the Carriage Manufacture there … 126

Up-town and Downtown—East End and West End—Master Stebbins—A Model Schoolmaster—The School-house—Administration of the School—Zeek Sanford—Schoolrooms—Arithmetic—History—Grammar—Anecdote of G…. H……—Country Schools of New England in these Days—Master Stebbins’s Scholars … 138

Horsemanship—Bige’s Adventures—A Dead Shot—A Race—Academical Honors— Charles Chatterbox—My Father’s School—My Exercises in Latin—Tityre tu patulæ, etc.—Rambles—Literary Aspirations—My Mother—Family Worship—Standing and Kneeling at Prayer—Anecdotes—Our Philistine Temple … 147

My Father’s Library—Children’s Books—The New England, Primer and Westminster Catechism—Toy Books—Nursery Books—Moral Effect of these—Hannah Mare’s Moral Repository—The Shepherd of Salisbury Plain—Visit to Barley-wood—First Idea of the Parley Books—Impressions of Big Books and Little Books—A Comparison of the Old Book and the New Books for Children and Youth—A Modern Juvenile Bookstore in Broadway … 164

-----

p. 7

The Clergymen of Fairfield County—The Minister’s House a Minister’s Tavern—Dr. Ripley, of Green’s-farms—Dr. Lewis, of Horseneck—Dr. Burnett, of Norwalk—Mr. Swan—Mr. Noyes—Mr. Elliott, of Fairfield—Mr. Mitchell, of New Canaan—A Poet-Deacon—Dr. Blatchford, the Clairvoyant—Mr. Bartlett, of Reading—Mr. Camp, of Ridgebury—Mr. Smith, of Stamford—Mr. Waterman, of Bridgeport, &c.—Manners of the Clergy of Fairfield County—Their Character—Anecdote of the Laughing D. D.—The Coming Storm … 175

Ideas of the Pilgrim Fathers—Progress of Toleration—Episcopacy—Bishop Seabury—Dr. Duché—Methodism in America,—In Connecticut—Anecdotes—Lorenzo Dow—The Wolf in my Father’s Fold … 186

The Three Deacons … 218

The Federalist and the Democrat—Colonel Bradley and General King—Comparison of New England with European Villages … 229

The Ingersolls—Rev. Jonathan Ingersoll—Lieutenant-governor Ingersoll—New Haven Belles—A chivalrous Virginian among the Connecticut D. D.’s—Grace Ingersoll—A New Haven Girl at Napoleon’s Court—Real Romance—A Puritan in a Convent … 248

Mat Olmstead, the Town Wit—The Salamander Hat—The Great Eclipse—Sharp Logic—Lieutenant Smith, the Town Philosopher—The Purchase of Louisiana—Lewis and Clarke’s Exploring Expedition—The Great Meteor—Hamilton and Burr—The Leopard and the Chesapeake—Fulton’s Steamboats—Granther Baldwin, the Village Miser—Sarah Bishop, the Hermitess … 265

A Long Farewell—A Return—Ridgefield as it is—The Past and Present Compared … 299

Farewell to Ridgefield—Farewell to Home—Danbury—My new Vocation—A Revolutionary Patriarch—Life in a Country Store My Brother-in-law—Lawyer Hatch … 323

Visit to New Haven—The City—Yale College—My Uncle’s House—John Allen—First view of the Ocean—The Court-house—Dr. Dwight—Professor Silliman—Chemistry, Mineralogy, Geology—Anecdote of Colonel Gibbs—Eli Whitney—The Cotton-gin—The Gun-factory … 3[38]

Durham—History of Connecticut—Distinguished Families of Durham—The Chaunceys, Wadsworths, Lymans, Goodriches, Austins, &c.—Woodbury—How Romance becomes History—Rev. Noah Benedict—Judge Smith … 368

-----

p. 8

The Cold Winter and a Sharp Side—Description of Danbury—The Hat Manufactory—The Sandimanians—Gen. Wooster’s Monument—Death of my Brother-in-law—Master White—Mathematics—Farewell to Danbury … 393

Farewell to Danbury—Hartford—My first Master and His Family—Merino Sheep—A Wind-up—Another Change—My new Employer—A new Era in Life—George Sheldon—Franklin’s Biography … 403

My Situation under my new Master—Discontent—Humiliating Discoveries—Desire to quit Trade and go to College—Undertake to Reeducate myself—A Long Struggle—Partial Success—Infidelity—The World without a God—Existence, Nature, Life, all contradictions, without Revealed Religion—Return after long Wanderings … 417

Hartford forty years ago—The Hartford Wits—Hartford at the present time—The Declaration of War in 1812—Baltimore Riots—Fading in New England—Embargo—Non-intercourse, &c.—Democratic Doctrine that Opposition is Treason … 435

Specks of War in the Atmosphere—The First Year—Operations on the Land and on the Sea—The Wickedness of the Federalists—The Second Year—The Connecticut Militia—Decatur driven into the Thames—Connecticut in trouble—I become a Soldier—My First and Last Campaign … 451

Description of New London—Fort Trumbull—Fort Griswold—The British Fleet—Decatur and his Ships in the Thames—Commodore Hardy—Letters from Home—Performances of the Hartford Company—Fishing—A few British Broadsides—Apprehensions of an Attack—Great Preparations—Sober Second Thoughts—On Guard—A Suspicious Customer—Alarm, alarm!—Company called out—Expectations of instant Battle—Corporal T.’s Nightmare—Consequences—Influence of Camp Life—Return to Hartford—Land Warrants—Blue Lights—Decatur, Biddle, and Jones … 466

Continuation of the War—The Creeks subdued—Battles of Chippewa and Bridgewater—Capture of Washington—Bladensburg Races— Humiliation of the President—Defense of Baltimore—The Star-spangled Banner—Ravages of the Coast by the British Fleet—Downfall of Napoleon—Scarcity of Money—Rag Money—Bankruptcy of the National Treasury—The Specie Bank-note, or Mr. Sharp and Mr. Sharper—Scarcity and exorbitant Prices of British Goods—Depression of all Kinds of Business—My Pocket-book Factory—Naval and Land Battle at Plattsburg—Universal Gloom—State of New England—Anxiety of the Administration—Their Instructions to the Peace Commissioners—Battle of New Orleans—Peace—Illuminations and Rejoicings … 488

Appendix. … 515

-----

[p. 9]

IN A SERIES OF

FAMILIAR LETTERS TO A FRIEND.

——

LETTER I.

Introductory and Explanatory.

My dear C******

A little thin, sheet of paper, with a frail wafer seal, and inscribed with various hieroglyphical symbols, among which I see the postmark of Albany, just been laid upon my table. I have opened it, and find it to be a second letter from you. Think of the pilgrimage of this innocent waif, unprotected save by faith in man and the mail, setting out upon a voyage from the banks of the Hudson, and coming straight to me at Courbevoie, just without the walls of Paris, a distance of three thousand miles!

And yet this miracle is wrought every day, every hour. I am lingering here, partly because I have taken a lease of a house and furnished it, and therefore I can not well afford to leave it at present. I am pursuing my literary labors, and such are the fa-

-----

p. 10

cilities of intercourse, by means of these little red-lipped messengers, like this I have just received from you, that I can almost as well prosecute my labors here as at home. Could I get rid of all those associations which bind a man to his birth-land; could I appease that consciousness which whispers in my ear, that the allegiance of every true man, free to follow his choice, is due to his country and his kindred, I might perhaps continue here for the remainder of my life.

My little pavilion, situated upon an elevated slope formed of the upper bank of the Seine, gives me a view of the unrivaled valley that winds between Saint Cloud and Asnières; it shows me Paris in the near distance—Montmartre to the left, and the Arch of Triumph to the right. In the rear, close at hand, is our suburban village, having the aspect of a little withered city. Around are several chateaus, and from the terraced roof of my house—which is arranged for a promenade—I can look into their gardens and pleasure-grounds, sparkling with fountains and glowing with fruits and flowers. A walk of a few rods brings me to the bank of the Seine, where boatmen are ever ready to give the pleasure-seeker a row or a sail; in ten minutes by rail, or an hour on foot, I can be in Paris. In about the same time I may be sauntering in the Avenue de Neuilly, the Bois de Boulogne, or the galleries of Versailles. My rent is but about four hundred dollars a year, with the freedom of the gar-

-----

p. 11

dens and grounds of the chateau, of which my residence is an appendage. It is the nature of this climate to bring no excessive cold and no extreme heat. You may sit upon the grass till midnight of a summer evening, and fear no chills or fever; no troops of flies, instinctively knowing your weak point, settle upon your nose and disturb your morning nap or your afternoon siesta; no elvish mosquitoes invade the sanctity of your sleep, and force you to listen to their detestable serenade, and then make you pay for it, as if you had ordered the entertainment. If there be a place on earth combining economy and comfort—where one may be quiet, and yet in the very midst of life—it is here. Why, then, should I not remain? In one word, because I would rather be at home. This is, indeed, a charming country, but it is not mine. I could never reconcile myself to the idea of spending my life in a foreign land.

I am therefore preparing to return to New York the next summer, with the intention of making that city my permanent residence. In the mean time, I am not idle, for, as you know, the needs of my family require me to continue grinding at the mill. Besides one or two other trifling engagements, I have actually determined upon carrying out your suggestion, that I should write a memoir of my life and times— a panorama of my observations and experience. You encourage me with the idea that an account of my life, common-place as it has been, will find readers,

-----

p. 12

and at the same time, your recommendation naturally suggests a form in which this may be given to the public, divested of the air of egotism which generally belongs to autobiography. I may write my history in the form of letters to you, and thus tell a familiar story in a familiar way—to an old friend.

I take due note of what you recommend—that I should make my work essentially a personal narrative. You suggest that so long as the great study of mankind is man, so long any life—supposing it to be not positively vicious—if truly and frankly portrayed, will prove amusing, perhaps instructive. I admit the force of this, and it has its due influence upon me; but still I shall not make my book, either wholly or mainly, a personal memoir. I have no grudges to gratify, no by-blows to give, no apologies to make, no explanations to offer—at least none which could reasonably find place in a work like this. I have no ambition which could be subserved by a publication of a merely personal nature: to confess the truth, I should rather feel a sense of humiliation at appearing thus in print, as it would inevitably suggest the idea of pretense beyond performance.

What I propose is this: venturing to presume upon your sympathy thus far, I invite you to go with me, in imagination, over the principle scenes I have witnessed, while I endeavor to make you share in the impressions they produced upon my own mind. Thus I shall carry you back to my early days, to my native

-----

p. 13

village, the “sweet Auburn” of my young fancy, and present to you the homely country life in which I was born and bred. Those pastoral scenes were epics to my childhood; and though the heroes and heroines consisted mainly of the deacons of my father’s church and the school-ma’ams that taught me to read and write, I shall still hope to inspire you with a portion of the loving reverence with which I regard their memories. I shall endeavor to interest you in some of the household customs of our New England country life, fifty years ago, when the Adams delved and the Eves span, and thought it no stain upon their gentility. I shall let you into the intimacy of my boyhood, and permit you to witness my failures as well as my triumphs. In this the first stage of my career, I shall rely upon your good nature, in permitting me to tell my story in my own way. If I make these early scenes and incidents the themes of a little moralizing, I hope for your indulgence.

From this period, as the horizon of my experience becomes somewhat enlarged, I may hope to interest you in the topics that naturally come under review. As you are well acquainted with the outline of my life, I do not deem it necessary to forewarn you that my history presents little that is out of the beaten track of common experience. I have no marvels to tell, no secrets to unfold, no riddles to solve. It is true that in the course of a long and busy career, I have seen a variety of men and things, and had my share

-----

p. 14

of vicissitudes in the shifting drama of life; still the interest of my story must depend less upon the importance of my revelations than the sympathy which naturally belongs to a personal narrative. I am perfectly aware that in regard to many of the events I shall have occasion to describe, many of the scenes I shall portray, many of the characters I shall bring upon the stage, my connection was only that of a spectator; nevertheless, I shall hope to impart to them a certain life and reality by arranging them continuously upon the thread of my remembrances.

This, then, is my preface; as the wind and weather of my humor shall favor, I intend to proceed and send you letter by letter as I write. After a few specimens, I shall ask your opinion; if favorable, I shall go on, if otherwise, I shall abandon the enterprise. I am determined, if I publish the work, to make you responsible for my success before the public.

S. G. Goodrich.

Courbevoie, near Paris, June, 1854.

-----

p. 15

LETTER II.

Geography and Chronology—The Old Brown House—Grandfathers—Ridgefield—The Meeting-House—Parson Mead—Keeler’s Tavern—Lieutenant Smith—The Cannon-Ball.

My dear C******

It is said that geography and chronology are the two eyes of history: hence, I suppose that in any narrative which pretends to be in some degree historical, the when and where, as well as the how, should be distinctly presented. I am aware that a large part of mankind are wholly deficient in the bump of locality, and march through the world in utter indifference as to whether they are going north or south, east or west. With these, the sun may rise and set as it pleases, at any point of the compass; but for myself, I could never be happy, even in my bedroom or study, without knowing which way was north. You will expect, therefore, that in beginning my story, I make you distinctly acquainted with the place where I was born, as well as the objects which immediately surrounded it. If, indeed, throughout my narrative, I habitually regard geography and chronology, as essential elements of a story, you will at least understand that it is done by design and not by accident.

In the western part of the State of Connecticut, is

-----

p. 16

a small town by the name of Ridgefield.* This title is descriptive, and indicates the general form and position of the place. It is, in fact, a collection of hills, rolled into one general and commanding elevation. On the west is a ridge of mountains, forming the boundary between the States of Connecticut and New York; to the south the land spreads out in wooded undulations to Long Island Sound; east and north, a succession of hills, some rising up against the sky, and others fading away in the distance, bound the horizon. In this town, in an antiquated and rather dilapidated house of shingles and clapboards, I was born on the 19th of August, 1793.

My father, Samuel Goodrich, was minister of the First Congregational Church of that place, there being then, no other religious society and no other clergyman in the town, except at Ridgebury—the remote northern section, which was a separate parish. He was the son of Elizur Goodrich,† a distinguished minister of the same persuasion, at Durham, Connecticut. Two of his brothers were men of eminence—the late Chauncey Goodrich of Hartford, and Elizur Goodrich of New Haven. My mother was a daughter of John Ely,‡ a physician of Saybrook, whose name figures not unworthily in the annals of the revolutionary war.

I was the sixth child of a family of ten children,

-----

p. 17

two of whom died in infancy, and eight of whom lived to be married and settled in life. All but two of the latter are still living. My father’s annual salary for the first twenty-five years, and during his ministry at Ridgefield, averaged 120, old currency—that is, about four hundred dollars a year: the last twenty-five years, during which he was settled at Berlin, near Hartford, his stipend was about five hundred dollars a year. He was wholly without patrimony, and owing to peculiar circumstances, which will be hereafter explained, my mother had not even the ordinary outfit, as they began their married life. Yet they so brought up their family of eight children, that they all attained respectable positions in life, and at my father’s death, he left an estate of four thousand dollars.* These facts throw light upon the simple annals of a country clergyman in Connecticut, half a century ago; they also bear testimony to the thrifty energy and wise frugality of my parents, and especially of my mother, who was the guardian deity of the household.

Ridgefield† belongs to the county of Fairfield, and is now a handsome town, as well on account of its artificial as its natural advantages—with some 2000 inhabitants. It is fourteen miles from Long Island Sound—of which its many swelling hills afford charm-

-----

p. 18

ing views. The main street is a mile in length, and is now embellished with several handsome houses. About the middle of it there is, or was, some forty years ago, a white wooden meeting-house, which belonged to my father’s congregation. It stood in a small grassy square, the favorite pasture of numerous flocks of geese, and the frequent playground of schoolboys, especially of Saturday afternoons. Close by the front door ran the public road, and the pulpit, facing it, looked out upon it, in fair summer Sundays, as I well remember by a somewhat amusing incident.

In the contiguous town of Lower Salem, dwelt an aged minister by the name of Mead. He was all his life marked with eccentricity, and about these days of which I speak, his mind was rendered yet more erratic by a touch of paralysis. He was, however still able to preach, and on a certain Sunday, having exchanged with my father, he was in the pulpit and engaged in making his opening prayer. He had already begun his invocation, when David P., who was the Jehu of that generation, dashed by the front door, upon a horse—a clever animal of which he was but too proud—in a full, round trot. The echo of the clattering hoofs filled the church,—which being of shingles and clapboards was sonorous as a drum—and arrested the attention as well of the minister as the congregation, even before the rider had reached it. The minister was fond of horses—almost to frailty—and from the first, his practiced

-----

p. 19

ear perceived that the sounds came from a beast of bottom. When the animal shot by the door, he could not restrain his admiration, which was accordingly thrust into the very marrow of his prayer: “We pray thee, O Lord, in a particular and peculiar manner—that’s a real smart critter—to forgive us our manifold trespasses, in a particular and peculiar manner,” &c.

I have somewhere heard of a traveler on horseback, who, just at eventide, being uncertain of his road, inquired of a person he chanced to meet, the way to Barkhamstead.

“You are in Barkhamstead now,” was the reply.

“Yes, but where is the center of the place?”

“It hasn’t got any center.”

“Well but direct me to the tavern.”

“There ain’t any tavern.”

“Yes, but the meeting-house?”

“Why didn’t you ask that afore? There it is, over the hill!”

So, in those days, in Connecticut—as doubtless in other parts of New England—the meeting-house was the great geographical monument, the acknowledged meridian of every town and village. Even a place without a center or a tavern, had its house of worship, and this was its initial point of reckoning. It was, indeed, something more. It was the town-hall, where all public meetings were held, for civil purposes; it was the temple of religion, the ark of the covenant, the pillar of society—religious, social, and moral—

-----

p. 20

to the people around. It will not be considered strange then, if I look back to the meeting-house of Ridgefield, as not only a most revered edifice—covered with clapboards and shingles, though it was—but as in some sense the starting point of my existence. Here, at least, linger many of my most cherished remembrances.

A few rods to the south of this, there was, and still is, a tavern, kept in my day, by Squire Keeler. This institution ranked second only to the meeting-house; for the tavern of those days was generally the center of news, and the gathering place for balls, musical entertainments, public shows, &c.; and this particular tavern had special claims to notice. It was, in the first place, on the great thoroughfare of that day, between Boston and New York, and had become a general and favorite stopping-place for travelers. It was, moreover, kept by a hearty old gentleman, who united in his single person the varied functions of publican, postmaster, representative, justice of the peace, and I know not what else. He besides had a thrifty wife, whose praise was in all the land. She loved her customers, especially members of Congress, governors, and others in authority, who wore powder and white-top boots, and who migrated to and fro, in the lofty leisure of their own coaches. She was indeed a woman of mark, and her life has its moral. She scoured and scrubbed and kept things going, until she was seventy years old, at which time, du-

-----

p. 21

ring an epidemic, she was threatened with an attack. She, however, declared that she had not time to be sick, and kept on working, so that the disease passed her by, though it made sad havoc all around her—especially with more dainty dames, who had leisure to follow the fashion.

Besides all this, there was an historical interest attached to Keeler’s tavern, for deeply imbedded in the northeastern corner-post, there was a cannon-ball, planted there during the famous fight with the British in 1777. It was one of the chief historical monuments of the town, and was visited by all curious travelers who came that way.* Little can the present generation imagine with what glowing interest, what ecstatic wonder, what big round eyes, the rising generation of Ridgefield, half a century ago, listened to the account of the fight as given by Lieutenant Smith, himself a witness of the event and a participator of the conflict, sword in hand.

This personage, whom I shall have occasion again to introduce to my readers, was, in my time, a justice

-----

p. 22

of the peace, town librarian, and general oracle in such loose matters as geography, history, and law—then about as uncertain and unsettled in Ridgefield, as is now the fate of Sir John Franklin, or the longitude of Lilliput. He had a long, lean face; long, lank, silvery hair, and an unctuous, whining voice. With these advantages, he spoke with the authority of a seer, and especially in all things relating to the revolutionary war.

The agitating scenes of that event, so really great in itself, so unspeakably important to the country, had transpired some five and twenty years before. The existing generation of middle age, had all witnessed it; nearly all had shared in its vicissitudes. On every hand there were corporals, sergeants, lieutenants, captains, and colonels—no strutting fops in militia buckram, raw blue and buff, all fuss and feathers—but soldiers, men who had seen service and won laurels in the tented field. Every old man, every old woman had stories to tell, radiant with the vivid realities of personal observation or experience. Some had seen Washington, and some Old Put; one was at the capture of Ticonderoga under Ethan Allen; another was at Bennington, and actually heard old Stark say, “Victory this day, or my wife Molly is a widow!” Some were at the taking of Stony Point, and others in the sanguinary struggle of Monmouth. One had witnessed the execution of Andre, and another had been present at the capture of Burgoyne.

-----

p. 23

The time which had elapsed since these events, had served only to magnify and glorify these scenes, as well as the actors, especially in the imagination of the rising generation. If perchance we could now dig up, and galvanize into life, a contemporary of Julius Cæsar, who was present and saw him cross the Rubicon, and could tell us how he looked and what he said—we should listen with somewhat of the greedy wonder with which the boys of Ridgefield listened to Lieutenant Smith, when of a Saturday afternoon, seated on the stoop of Keeler’s tavern, he discoursed upon the discovery of America by Columbus, Braddock’s defeat, and the old French war—the latter a real epic, embellished with romantic episodes of Indian massacres and captivities. When he came to the Revolution, and spoke of the fight at Ridgefield, and punctuated his discourse with a present cannon-ball, sunk six inches deep in a corner-post of the very house in which we sat, you may well believe it was something more than words—it was, indeed, “action, action, glorious action!” How little can people nowadays—with curiosity trampled down by the march of mind and the schoolmaster abroad—comprehend or appreciate these things!

-----

p. 24

LETTER III.

The first Remembered Event—High Ridge—The Spy-glass—Sea and Mountain—The Peel—The Black Patch in the road.

My dear C******

You will perhaps forgive me for a little circumlocution, in the outset of my story. My desire is to carry you with me in my narrative, and make you see in imagination, what I have seen. This naturally requires a little effort—like that of the bird in rising from the ground, which turns his wing first to the right and then to the left, vigorously beating the atmosphere, in order to overcome the gravity which weighs the body down to earth, ere yet it feels the quickening impulse of a conscious launch upon the air.

My memory goes distinctly back to the year 1797, when I was four years old. At that time a great event happened—great in the near and narrow horizon of childhood: we removed from the Old House to the New House! This latter, situated on a road tending westward and branching from the main street, my father had just built; and it then appeared to me quite a stately mansion and very beautiful, inasmuch as it was painted red behind and white in front—most of the dwellings thereabouts being of

-----

p. 25

the dun complexion which pine-boards and chestnut-shingles assume, from exposure to the weather. Long after having been absent twenty years—I revisited this my early home, and found it shrunk into a very small and ordinary two-story dwelling, wholly divested of its paint, and scarcely thirty feet square.

This building, apart from all other dwellings, was situated on what is called High Ridge—a long hill, looking down upon the village, and commanding an extensive view of the surrounding country. From our upper windows, this was at once beautiful and diversified. On the south, as I have said, the hills sloped in a sea of undulations down to Long Island Sound, a distance of some fourteen miles. This beautiful sheet of water, like a strip of pale sky, with the island itself, more deeply tinted, beyond, was visible in fair weather, for a stretch of sixty miles, to the naked eye. The vessels—even the smaller ones, sloops, schooners, and fishing craft—could be seen, creeping like insects over the surface. With a spy-glass—and my father had one bequeathed to him by Nathan Kellogg, a sailor, who made rather a rough voyage of life, but anchored at last in the bosom of the church, as this bequest intimates—we could see the masts, sails, and rigging. It was a poor, dim affair, compared with modern instruments of the kind; but to me, its revelations of an element which then seemed as beautiful, as remote, and as mystical as the heavens, surpassed the wonders of

-----

p. 26

the firmament as since disclosed to my mind by Lord Rosse’s telescope.

To the west, at the distance of three miles, lay the undulating ridge of hills, cliffs, and precipices already mentioned, and which bear the name of West Mountain. They are some five hundred feet in height, and from our point of view had an imposing appearance. Beyond them, in the far distance, glimmered the ghost-like peaks of the Highlands along the Hudson. These two prominent features of the spreading landscape—the sea and the mountain, ever present, yet ever remote impressed themselves on my young imagination with all the enchantment which distance lends to the view. I have never lost my first love. Never, even now, do I catch a glimpse of either of these two rivals of nature, such as I first learned them by heart, but I feel a gush of emotion as if I had suddenly met with the cherished companions of my childhood. In after days, even the purple velvet of the Apennines and the poetic azure of the Mediterranean, have derived additional beauty to my imagination from mingling with these vivid associations of my childhood.

It was to the New House, then, thus situated, that we removed, as I have stated, when I was four years old. On that great occasion, every thing available for draft or burden was put in requisition; and I was permitted, or required, I forget which, to carry the peel, as it was then called, but which would now bear

-----

p. 27

the title of shovel. Birmingham had not then been heard of in those parts, or at least was a great way off; so this particular utensil had been forged expressly for my father by David Olmstead, the blacksmith, as was the custom in those days. I recollect it well, and can state that it was a sturdy piece of iron, the handle being four feet long, with a hemispherical knob at the end. As I carried it along, I doubtless felt a touch of that consciousness of power, which must have filled the breast of Samson as he bore off the gates of Gaza. I recollect perfectly well to have perspired under the operation, for the distance of our migration was half a mile, and the season was summer.

One thing more I remember: I was barefoot; and as we went up the lane which diverged from the main road to the house, we passed over a patch of earth, blackened by cinders, where my feet were hurt by pieces of melted glass and metal. I inquired what this meant, and was told that here a house was burned down* by the British troops already men-

-----

p. 28

tioned—and then in full retreat—as a signal to ships that awaited them on the Sound where they had landed, and where they intended to embark.

This detail may seem trifling, but it is not without significance. It was the custom in those days for boys to go barefoot in the mild season. I recollect few things in life more delightful than, in the spring, to cast away my shoes and stockings, and have a glorious scamper over the fields. Many a time contrary to the express injunctions of my mother, have I stolen this bliss, and many a time have I been punished by a severe cold for my imprudence, if not my disobedience. Yet the bliss then seemed a compensation for the retribution. In these exercises I felt as if stepping on air—as if leaping aloft on wings. I was so impressed with the exultant emotions thus experienced, that I repeated them a thousand times in happy, dreams, especially in my younger days. Even now, these visions sometimes come to me in sleep, though with a lurking consciousness that they are but a mockery of the past—sad monitors of the change which time has wrought upon me.

As to the black patch in the lane, that too had its meaning. The story of a house burned down by a foreign army, seized upon my imagination. Every time I passed the place, I ruminated upon it, and put a hundred questions as to how and when it happened. I was soon master of the whole story, and of other similar events which had occurred all over the

-----

p. 29

country. I was thus initiated into the spirit of that day, and which has never wholly subsided in our country, inasmuch as the war of the Revolution was alike unjust in its origin, and cruel as to the manner in which it was waged. It was, moreover, fought on our own soil, thus making the whole people share, personally, in its miseries. There was scarcely a family in Connecticut whom it did not visit, either immediately or remotely, with the shadows of mourning and desolation. The British nation, to whom this conflict was a foreign war, are slow to comprehend the depth and universality of the popular dislike of England, here in America. Could they know the familiar annals of our towns and villages—burned, plundered, sacked—with all the attendant horrors, for the avowed purpose of punishing a nation of rebels, and those rebels of their own kith and kin; could they be made acquainted with the deeds of those twenty thousand Hessians, sent hither by King George, and who have left their name in our language as a word signifying brigands, who sell their blood and commit murder, massacre, and rape for hire: could they thus read the history of minds and hearts, influenced at the fountains of life for several generations—they would perhaps comprehend, if they could not approve, the habitual distrust of British influence, which lingers among our people. At least, thus instructed, and bearing in mind what has since happened another war with England, in

-----

p. 30

which our own territory was the scene of conflict, together with the incessant hostility of the British press toward our manners, our institutions, our policy, our national character, manifested in every form, and from the beginning to the end—the people of England might in some degree comprehend what always strikes them with amazement, that love of England is not largely infused into our national character and habits of thought.

LETTER IV.

Education in New England—The Burial Ground of the Suicide—West Lane—Old Chichester—The School-House—The First Day at School—Aunt Delight—Lewis Olmstead—A Return after Twenty Years—Peter Parley and Mother Goose.

My dear C******

The devotion of the New-England people to education has been celebrated from time immemorial. In this trait of character, Connecticut was not behind the foremost of her sister puritans. Now, among the traditions of the days to which my narrative refers, there was one which set forth that the law of the land assigned to persons committing suicide, a burial-place where four roads met. I do not recollect that this popular notion was ever tested in Ridgefield, for

-----

p. 31

nobody in those innocent days, so far as I know, became weary of existence. Be this as it may, it is certain that the village school-house was often planted in the very spot supposed to be the privileged graveyard of suicides. The reason is plain enough: the roads were always of ample width at the crossings, and the narrowest of these spaces was sufficient for the little brown seminaries of learning. At the same time and this was doubtless the material point the land belonged to the town, and so the site would cost nothing. Such were the ideas of village education in enlightened New England half a century ago. Let those who deny the progress of society, compare this with the state of things at the present day.

About three-fourths of a mile from my father’s house, on the winding road to Lower Salem which I have already mentioned, and which bore the name of West Lane, was the school-house where I took my first lessons, and received the foundations of my very slender education. I have since been sometimes asked where I graduated: my reply has always been, “at West Lane.” Generally speaking, this has ended the inquiry, whether because my interlocutors have confounded this venerable institution with “Lane Seminary,” or have not thought it worth while to risk an exposure of their ignorance as to the college in which I was educated, I am unable to say.

The site of the school-house was a triangular piece

-----

p. 32

of land, measuring perhaps a rood in extent, and lying, according to the custom of those days, at the meeting of four roads. The ground hereabouts—as everywhere else in Ridgefield—was exceedingly stony, and in making the pathway the stones had been thrown out right and left, and there remained in heaps on either side, from generation to generation. All around was bleak and desolate. Loose, squat stone walls, with innumerable breaches, inclosed the adjacent fields. A few tufts of elder, with here and there a patch of briers and pokeweed, flourished in the gravelly soil. Not a tree, however, remained, save an aged chestnut, at the western angle of the space. This, certainly, had not been spared for shade or ornament, but probably because it would have cost too much labor to cut it down, for it was of ample girth. At all events it was the oasis in our desert during summer; and in autumn, as the burrs disclosed its fruit, it resembled a besieged city. The boys, like so many catapults, hurled at it stones and sticks, until every nut had capitulated.

Two houses only were at hand: one, surrounded by an ample barn, a teeming orchard, and an enormous wood-pile, belonged to Granther Baldwin; the other was the property of “Old Chich-es-ter,” an uncouth, unsocial being, whom everybody for some reason or other seemed to despise and shun. His house was of stone and of one story. He had a cow, which every year had a calf. He had a wife—filthy, un-

-----

p. 33

combed, and vaguely reported to have been brought from the old country. This is about the whole history of the man, so far as it is written in the authentic traditions of the parish. His premises, an acre in extent, consisted of a tongue of land between two of the converging roads. No boy, that I ever heard of, ventured to cast a stone, or to make an incursion into this territory, though it lay close to the school-house. I have often, in passing, peeped timidly over the walls, and caught glimpses of a stout man with a drab coat, drab breeches, and drab gaiters, glazed with ancient grease and long abrasion, prowling about the house; but never did I discover him outside of his own dominion. I know it was darkly intimated that he had been a tory, and was tarred and feathered in the revolutionary war, but as to the rest he was a perfect myth. Granther Baldwin was a character no less marked, but I must reserve his picture for a subsequent letter.

The school-house itself consisted of rough, unpainted clapboards, upon a wooden frame. It was plastered within, and contained two apartments—a little entry, taken out of a corner for a wardrobe, and the school-room proper. The chimney was of stone, and pointed with mortar, which, by the way, had been dug into a honeycomb by uneasy and enterprising penknives. The fireplace was six feet wide and four feet deep. The flue was so ample and so perpendicular, that the rain, sleet, and snow fell direct to the hearth.

-----

p. 34

In winter, the battle for life with green fizzling fuel, which was brought in sled lengths and cut up by the scholars, was a stern one. Not unfrequently, the wood, gushing with sap as it was, chanced to be out, and as there was no living without fire, the thermometer being ten or twenty degrees below zero, the school was dismissed, whereat all the scholars rejoiced aloud, not having the fear of the schoolmaster before their eyes.

It was the custom at this place, to have a woman’s school in the summer months, and this was attended only by young children. It was, in fact, what we now call a primary or infant school. In winter, a man was employed as teacher, and then the girls and boys of the neighborhood, up to the age of eighteen, or even twenty, were among the pupils. It was not uncommon, at this season, to have forty scholars crowded into this little building.

I was about six years old when I first went to school. My teacher was Aunt Delight, that is, Delight Benedict, a maiden lady of fifty, short and bent, of sallow complexion and solemn aspect. I remember the first day with perfect distinctness. I went alone for I was familiar with the road, it being that which passed by our old house. I carried a little basket, with bread and butter within, for my dinner, the same being covered over with a white cloth. When I had proceeded about half way, I lifted the cover, and debated whether I would not eat my din-

-----

p. 35

ner, then. I believe it was a sense of duty only that prevented my doing so, for in those happy days, I always had a keen appetite. Bread and butter were then infinitely superior to pâté de foie gras now; but still, thanks to my training, I had also a conscience. As my mother had given me the food for dinner, I did not think it right to convert it into lunch, even though I was strongly tempted.

I think we had seventeen scholars—boys and girls—mostly of my own age. Among them were some of my after companions. I have since met several of them—one at Savannah, and two at Mobile, respectably established, and with families around them. Some remain, and are now among the gray old men of the town; the names of others I have seen inscribed on the tombstones of their native village. And the rest—where are they ?

The school being organized, we were all seated upon benches, made of what were called slabs—that is, boards having the exterior or rounded part of the log on one side: as they were useless for other purposes, these were converted into school-benches, the rounded part down. They had each four supports, consisting of straddling wooden legs, set into augur-holes. Our own legs swayed in the air, for they were too short to touch the floor. Oh, what an awe fell over me, when we were all seated and silence reigned around!

The children were called up, one by one, to Aunt

-----

p. 36

Delight, who sat on a low chair, and required each, as a preliminary, to make his manners, consisting in a small sudden nod or jerk of the head. She then placed the spelling-book—which was Dilworth’s—before the pupil, and with a buck-handled penknife pointed, one by one, to the letters of the alphabet saying, “What’s that?” If the child knew his letters the “what’s that?” very soon ran on thus:

“What’s that?”

“A.”

“ ’Stha-a-t?”

“B.”

“Sna-a-a-t?”

“C.”

“Sna-a-a-t?”

“D.”

“Sna-a-a-t?”

“E.” &c.

I looked upon these operations with intense curiosity and no small respect, until my own turn came. I went up to the school-mistress with some emotion, and when she said, rather spitefully, as I thought, “Make your obeisance!” my little intellects all fled away, and I did nothing. Having waited a second, gazing at me with indignation, she laid her hand on the top of my head, and gave, it a jerk which made my teeth clash. I believe I bit my tongue a little; at all events, my sense of dignity was offended, and when she pointed to A, and asked what it was, it

-----

-----

p. 37

swam before me dim and hazy, and as big as a full moon. She repeated the question, but I was doggedly silent. Again, a third time, she said, “What’s that?” I replied: “Why don’t you tell me what it is? I didn’t come here to learn you your letters!” I have not the slightest remembrance of this, for my brains were all a-woolgathering; but as Aunt Delight affirmed it to be a fact, and it passed into a tradition, I put it in. I may have told this story some years ago in one of my books, imputing it to a fictitious hero, yet this is its true origin, according to my recollection.

What immediately followed I do not clearly remember, but one result is distinctly traced in my memory. In the evening of this eventful day, the school-mistress paid my parents a visit, and recounted to their astonished ears this, my awful contempt of authority. My father, after hearing the story, got up and went away; but my mother, who was a careful disciplinarian, told me not to do so again! I always had a suspicion that both of them smiled on one side of their faces, even while they seemed to sympathize with the old petticoat and pen-knife pedagogue, on the other; still I do not affirm it; for I am bound to say, of both my parents, that I never knew them, even in trifles, say one thing while they meant another.

I believe I achieved the alphabet that summer, but my after progress, for a long time, I do not remember. Two years later I went to the winter-school at the

-----

p. 38

same place, kept by Lewis Olmstead—a man who had a call for plowing, mowing, carting manure, &c., in summer, and for teaching school in the winter, with a talent for music at all seasons, wherefore he became chorister upon occasion, when, peradventure, Deacon Hawley could not officiate. He was a celebrity in ciphering, and ’Squire Seymour declared that he was the greatest “arithmeticker” in Fairfield county. All I remember of his person is his hand, which seemed to me as big as Goliah’s, judging by the claps of thunder it made in my ears on one or two occasions.

The next step of my progress which is marked in my memory, is the spelling of words of two syllables. I did not go very regularly to school, but by the time I was ten years old I had learned to write, and had made a little progress in arithmetic. There was not a grammar, a geography, or a history of any kind in the school. Reading, writing, and arithmetic were the only things taught, and these very indifferently not wholly from the stupidity of the teacher, but because he had forty scholars, and the standards of the age required no more than he performed. I did as well as the other scholars, certainly no better. I had excellent health and joyous spirits; in leaping, running, and wrestling I had but one superior of my age, and that was Stephen Olmstead, a snug-built fellow, smaller than myself, and who, despite our rivalry, was my chosen friend and companion. I seemed to live

-----

p. 39

for play: alas! how the world has changed since I have discovered that we live to agonize over study, work, care, ambition, disappointment, and then—?

As I shall not have occasion again, formally, to introduce this seminary into my narrative, I may as well close my account of it now. After I had left my native town for some twenty years, I returned and paid it a visit. Among the monuments that stood high in my memory was the West Lane school-house. Unconsciously carrying with me the measures of childhood, I had supposed it to be at least thirty feet square; how had it dwindled when I came to estimate it by the new standards I had formed! It was in all things the same, yet wholly changed to me. What I had deemed a respectable edifice, as it now stood before me was only a weather-beaten little shed, which, upon being measured, I found to be less than twenty feet square. It happened to be a warm, summer day, and I ventured to enter the place. I found a girl, some eighteen years old, keeping a ma’am school for about twenty scholars, some of whom were studying Parley’s Geography. The mistress was the daughter of one of my schoolmates, and some of the boys and girls were grandchildren of the little brood which gathered under the wing of Aunt Delight, when I was an a-b-c-darian. None of them, not even the school-mistress, had ever heard of me. The name of my father, as having ministered unto the people of Ridgefield in some bygone

-----

p. 40

age, was faintly traced in their recollection. As to Peter Parley, whose geography they were learning—they supposed him some decrepit old gentleman hobbling about on a crutch, a long way off, for whom nevertheless, they had a certain affection, inasmuch as he had made geography into a story-book. The frontispiece-picture of the old fellow, with his gouty foot in a chair, threatening the boys that if they touched his tender toe, he would tell them no more stories—secured their respect, and placed him among the saints in the calendar of their young hearts. Well, thought I, if this goes on I may yet rival Mother Goose!

-----

p. 41

LETTER V.

The Joyous Nature of Childhood—Drawbacks—The Small-Pox—The Pest-House—Our House a Hospital—Inoculation—The Force of Early Impressions—Rogers’ Pleasures of Memory—My First Whistle—My Sister’s Recollections of a Sunday Afternoon—The Song of Kalewala— Poetic Character of Early Life—Obligations to make Childhood Happy—Beautiful Instinct of Mothers—Improvements in the Training of Children Suggested—Example of our Saviour—The Family a Divine Institution—Christian Marriage.

My dear C******

I hope you will not imagine that I am thinking too little of your amusement and too much of my own, if I stop a few moments to note the lively recollections I entertain of the joyousness of my early life, and not of mine only, but that of my playmates and companions. In looking back to those early days, the whole circle of the seasons seems to me almost like one unbroken morning of pleasure.

I was of course subjected to the usual crosses incident to my age—those painful and mysterious visitations sent upon children—the measles, mumps, whooping-cough, and the like—usually regarded as retributions for the false step of our mother Eve in the Garden; but they have almost passed from my memory, as if overflowed and borne away by the general drift of happiness which filled my bosom. Among these calamities, one monument alone remains—the small-pox. It was in the year 1798, as I

-----

p. 42

well remember, that my father’s house was converted into a hospital, or, as it was then called, a “pest-house,” where, with some dozen other children, I was inoculated for this disease, then the scourge and terror of the world.

It will be remembered that Jenner published his first memoir upon vaccination about this period, but his discoveries were generally repudiated as mere charlatanism, for some time after. There were regular small-pox hospitals in different parts of New England, usually in isolated situations, so as not to risk dissemination of the dreaded infection. One of these, and quite the most celebrated of its time, had been established by my maternal grandfather upon Duck Island, lying off the present town of West Brook—then called Pochaug—in Long Island Sound; but it had been destroyed by the British during the Revolution, and was never revived. There was one upon the northern shore of Long Island, and doubtless many others; but as it was often inconvenient to send children to these places, several families would unite and convert one house, favorably situated, into a temporary hospital, for the inoculation of such as needed it. It was in pursuance of this custom that our habitation was selected, on the present occasion, as the scene of this somewhat awful process.

There were many circumstances which contributed to impress this event upon my mind. In the first place, there was a sort of popular horror of the “pest-

-----

p. 43

house,” not merely because of the virulent nature of small-pox, but because of a common superstitious feeling in the community—though chiefly confined to the ignorant classes—that voluntarily to create the disease, was contrary to nature, and a plain tempting of Providence. In their view, if death ensued, it was esteemed little better than murder. Thus, as our house was being put in order for the coming scene, and as the subjects of the fearful experiment were gathering in, a gloom pervaded all countenances, and its shadow naturally fell upon me.

The lane in which our house was situated

was fenced up, north and south, so as to cut off all intercourse with the

world around. A flag was raised, and upon it were inscribed the ominous

words ![]() “SMALLPOX.” My uncle and aunt,

from New Haven, arrived with

their three children.* Half a dozen others of

the neighborhood were gathered together, making, with our own children,

somewhat over a dozen subjects for the experiment. When all was ready, like

Noah and his family we were shut in. Provisions were deposited in a basket

at a point agreed upon, down the lane. Thus, we were cut off from the

world, excepting only that Dr. Perry, the physician, ventured to visit us in

our fell dominion.

“SMALLPOX.” My uncle and aunt,

from New Haven, arrived with

their three children.* Half a dozen others of

the neighborhood were gathered together, making, with our own children,

somewhat over a dozen subjects for the experiment. When all was ready, like

Noah and his family we were shut in. Provisions were deposited in a basket

at a point agreed upon, down the lane. Thus, we were cut off from the

world, excepting only that Dr. Perry, the physician, ventured to visit us in

our fell dominion.

As to myself, the disease passed lightly over, leav-

-----

p. 44

ing, however, its indisputable autographs upon various part of my body.* Were it not for these testimonials, I should almost suspect that I had escaped the disease, for I only remember, among my symptoms and my sufferings, a little headache, and the privation of salt and butter upon my hasty-pudding. My restoration to these privileges I distinctly recollect: doubtless these gave me more pleasure than the clean bill of health which they implied. Several of the patients suffered severely, and among them my brother and one of my cousins. The latter, in a recent conversation upon the subject, claimed the honor of two thousand pustules, and was not a little humbled when, by documentary evidence, they were reduced to two hundred.

Yet, while it is evident that I was subjected to the usual drawbacks upon the happiness of childhood, these were, in fact, so few as to have passed away from my mind, leaving in my memory only the general tide of life, seeming, as I look back, to have been one bright current of enjoyment, flowing

-----

p. 45

amid flowers, and all in the company of companions as happy and jubilant as myself. By a beautiful alchemy of the heart, the clouds of early life appear afterward to be only accessories to the universal spring-tide of pleasure. Even this dark episode of the pest-house, stands in my memory as rather an interesting event, partly because there was something strange and romantic about it, and partly because it is the office of the imagination to gild with sunshine even the clouds of the past.

In all this, my experience was in no way peculiar: I was but a representation of childhood in all countries and ages. I do not forget the instances in which children are subjected to misfortune, nor the moral obliquity which is in every childish heart. But making due allowance for the shadows thus cast upon the spring of life, its general current is such as I have described.

It has been oracularly said that the child is father of the man. If it is meant that men fulfill the promises of childhood, it is not true; for so far as my observation goes, not one child in five, when grown up, is altogether what was expected of him. If it is meant that the influences operating upon children ordinarily determine their future fate, it is doubtless correct; though I may remark, by the way, that it is rather an obscure mode of saying what had been happily expressed by Solomon, thousands of years ago.

But why is it that early impressions are thus wing-

-----

p. 46

ed with fate? Partly because of the plastic character of young life, and partly also because of the vividness, sincerity, and intensity of its conceptions. And these, be it remembered, are always pleasurable, unless some extraneous incident or accident intervenes to thwart the tendency of nature. The heart of childhood as readily inclines to flow in a current of enjoyment as water to run down hill. Hence it is, that in a majority of cases, or at least in a large proportion of cases, the remembrances of childhood are like those I have described—not only vivid and glowing, but cheerful and joyous.

As to this fullness and intensity of youthful impressions, every mind can furnish examples: all true poets recognize it; most celebrate it. Who can not remember particular places—such as hillsides, valleys, lawns; particular things—as rocks, trees, brooks; particular times and seasons— which have become fixed in the mind, and consecrated in the heart for all future time, by association with the ardent and glowing thoughts or experiences of childhood? Often a single incident, one momentary impression, is indelibly stamped as upon a die of steel. Let me take an example in my own childish remembrance. There was a willow-tree near my father’s house, which was graven on my memory by a particular circumstance: from this my brother cut a branch and made me a whistle of it—the first I remember to have possessed. The form of this tree, and all

-----

p. 47

the surrounding objects, as well as the day of the week and the season of the year, have lived from that hour in my memory. In a similar way, I remember a multitude of other familiar objects, all suggesting similar associations and recollections. Rogers, in his beautiful poem, the “Pleasures of Memory,” recognizes this vividness of early impressions, in supposing a person, after an absence of many years, to visit the site of the school-house of his early days—now in decay and ruin. As he passes over the place,

“Up springs, at every step, to claim a tear,

Some little friendship form’d in childhood here;

And not the lightest leaf but trembling teems

With golden visions and romantic dreams.”

I was recently conversing with my sister M….. upon this subject, and entertaining the views I have here expressed, she recited to me, as illustrative of her experience, some lines she had composed several years ago, but which she had not thought worth committing to paper. I requested a copy, which she furnished me, and I here insert them. They are designed to express the thoughts suggested by the recollection of a particular family scene, of a Sunday afternoon, which, for some reason or other, had been indelibly impressed upon her young mind.

-----

p. 48

A REMEMBERED SABBATH EVENING OF MY CHILDHOOD.

Oh! let me weave one song to-night,

For the spell is on me now;

And thoughts come thronging thick and bright,

All fresh and rosy with the light

Of childhood’s early glow.

They hurry from out the forgotten past,

Through the gather’d mist of years—

From the halls of Memory, dim and vast,

Where they have buried lain in the shadows cast

By recent joy or fears.

Say not mine is a thoughtful brow,

Furrow’d by care and pain;

My childhood’s curls seem over it now,

As they lay there years and years ago—

And I am a child again.

And I am again in my childhood’s home,

Which looks on the distant sea;

And the loved and lost—they come—they come!

To the old but well-remember’d room,

And I sit by my father’s knee.

’Tis the Sabbath evening hour of prayer;

And in the accustom’d place

Is my Father, with calm, benignant air:

Each brother and sister too is there,

And my Mother, with stately grace.

And with the rest comes a dark-eyed child—

The youngest of all is she,

Bringing her friend and playmate wild

In her dimpled arms, and with warnings mild

Checking its sportive glee.

-----

p. 49

And well could my young heart sympathize

With all I saw her do:

With the thought which danced in those laughing eyes,

Veil’d by a look demure and wise,—

That her kitten should join the service too.

And though glad I came at my father’s call,

My thoughts had much to do

With the whispering leaves of the poplar tall,

And the checker’d light on the whitewashed wall,

And the pigeons’ loving coo.

And I watch’d the banish’d kitten’s bound,

As it frolick’d to and fro;

And wish’d the spyglass could be found,

That I might see on the distant Sound

The tall ships come and go.

Through the open door my stealthy gaze

Sought the shadows, long and still;

When sudden the sun’s departing rays

Set the church windows all a-blaze,

On Greenfield’s* distant hill.

But new and wondering thoughts awoke,

Like morning from the night,

As, with deeply reverent voice and look,

My father read from the Holy Book,

By that Sabbath’s waning light.

He read of Creation’s early birth—

This vast and wondrous frame—

How “in the beginning" the Heavens and Earth

From the formless void were order’d forth,

And how they obedient came.

-----

p. 50

How Darkness lay like a heavy pall

On the face of the silent deep,

Till, answering to the Almighty call,

Light came, and spread, and waken’d all

From that deep and brooding sleep.

Oh! ever as sinks the Sabbath sun

In the glowing summer skies,

My father’s voice, my mother’s look,

Blent with the words of the Holy Book,

Upon my memory rise.

For then were traced on the mystic scroll

Of deathless imagery,

Deep hidden within my secret soul,

Which eternity only will fully unroll—

Some lines of my destiny !

The impressibility of youth, and the depth and earnestness of its conceptions, are beautifully suggested in the opening passage of the famous Finnish poem, the epic song of Kalewala. The lines are as follows:

“These the words we have received—

These, the songs we do inherit,

Are of Wainämöimen’s girdle—

From the forge of Ilmarinen,

Of the sword of Kankoinieli,

Of the bow of Youkanhainen,

Of the borders of the North-fields,

Of the plains of Kalewala.

“These my father sang aforetime,

As he chipped the hatchet’s handle

These were taught me by my mother

-----

p. 51

As she twirled her flying spindles,

When I on the floor was sporting,

Bound her knee was gayly dancing,

As a pitiable weakling—

As a weakling small of stature.

Never failed these wondrous stories,

Told of Sampo, told of Louhi:

Old grew Sampo in the stories;

Louhi vanished with her magic;

In the songs Wiunen perished:

In the play died Lemminkainen.

“There are many other stories,

Magic sayings which I learned,

Which I gathered by the wayside,

Culled amid the heather-blossoms,

Rifled from the bushy copses.

From the bending twigs I pluck’d them,

Plucked them from the tender grasses,

When a shepherd-boy I sauntered,

As a lad upon the pastures,

On the honey-bearing meadows,

On the gold-illumined hillock,

Following black Muurikki

At the side of spotted Kimmo.

“Songs the very coldness gave me,

Music found I in the rain-drops;

Other songs the winds brought to me,

Other songs, the ocean-billows;

Birds, by singing in the branches,

And the tree-top spoke in whispers.”

Thus in early life all nature is poetry: childhood and youth are indeed one continuous poem. In most cases this ecstasy of emotion and conception passes

-----

p. 52

away without our special notice. A it dies out from the memory, but passages are written upon the heart in lines of light and power, that can not be effaced. These become woven into the texture of the soul, and give character to it for time—perchance for eternity. The whole fountain of the mind, like some mineral spring, reaching to the interior elements of the earth—is imbued with ingredients which make its current sweet or bitter forever.

Pray excuse me for making a few suggestions upon these facts:—even if they seem like sermonizing. If early life is thus happy in its general current—in its nature and tendency—surely it is well and wise for those who have the care of children, to see in it the design of the Creator, and to follow the lead He has thus given. If God places our offspring in Eden, let us not causeless or carelessly take them out of it. It is certainly a mistake to consider childhood and youth—the first twenty years of life—as only a period of constraint and discipline. This is one-third part of existence—to a majority, it is more than the half of life. It is the only portion which seems made for unalloyed enjoyment. It is the morning, and all is sunshine: the after part of the day is necessarily devoted to toil and care, and that too amid clouds, and at last, beneath the shadows of approaching night. Let us not, then, presume to mar this birthright of bliss.

You will not suspect me to mean that government,

-----

p. 53

discipline, instruction, are to be withheld. These, are indispensable, but they should all be reconciled with the happy flow of life. This is, in fact, often attained by the instinct of mothers, whom God has given grace to combine government and indulgence, discipline and encouragement in such happy mixture, and measure, as to check the weeds, and foster the fruits, of the soul. It is not always done: it is not done perfectly, perhaps, in a single case. Yet I can not doubt that—despite all the difficulties which poverty, and ignorance, and sin impose upon the world—a majority of mothers do in fact temper their conduct to their children, so as, on the whole, to exercise, in a large degree, a saving, redeeming, regenerating influence upon them.

Nevertheless, there is room for improvement. There are too many persons who look upon children as reprobate—too many who regard the rod as the rule, not the exception. Some imagine that the whole business of education lies in study, and that to cram the mind is to enrich it. Some, indeed, are indifferent, and think even less of the moral growth and improvement of their children, than they do of the growth and improvement of their cattle. I think there are still others, who dislike children—who are annoyed by their presence, impatient of their little caprices, and regardless of their virtues; who only see their foibles, and would always confine them to the nursery. Even the Disciples of Christ seem not to

-----

p. 54

have been superior to this common feeling. The answer of our Saviour was at once a rebuke and a lesson. “Suffer the little children to come unto me, and forbid them not, for of such is the kingdom of heaven.” There is profound theology—there is deep, touching, divine humanity in this. Children are not reprobate: they are docile and teachable, with thoughts and emotions so pure as to breathe of heaven. They are cheerful, happy; their presence was healthful, even to the “Man of Sorrows and acquainted with grief!”

It is in this last aspect that I particularly wish to present this subject. Children, no doubt, impose burdens upon their parents. No words can express the weight of care which often presses “upon the heart of the mother—in the deep watches of the night, in moments of despondency, in periods of feeble health, in the pinches of poverty, in the trying, dark days of the spirit—as to the future prospects of her offspring. Anxieties for their welfare, temporal and eternal, often seem to wring the very heart, drop by drop, of its blood. And yet, all things considered, children are the great blessing of the household. They impose cares, but they elevate all hearts around them. They cultivate unselfish and therefore purifying feelings: they cheer the old, by reviving recollections of early life; they excite the young, by kindly fellowship and emulous sympathy. Without children, the world would be like a forest of old oaks, gnarled,

-----

p. 55

groaning, and fretful in the desolation of winter. For myself, I can say, that children are the best of playmates when I am well with the world, and they are the best of medicine, when I am sick and weary of it. It is children, here in the family, that are thus a blessing: not the children of a community, as in Sparta, for there they were educated to crime. In every community, where they are not the charge of the parents, and especially of the mother, they would, I think, infallibly become reprobates. The family seems to me a divine institution. Marriage, sanctioned by religion, is its bond: children its fruition. No statesman, no founder of a religion, no reformer—after innumerable attempts—has given the world a substitute for Christian Marriage and that institution which follows—the Family. It is, up to this era of our world, the anchor of society, the fountain of love and hope and dignity in man and human society. Those who attempt to overturn it, are, I think, working against the Almighty.

------

p. 56

LETTER VI.

The Inner Life of Towns—Physical Aspect and Character of Ridgefield—Effects of Cultivation upon Climate—Energetic Character of the First Settlers of Ridgefield—Classes of the People as to Descent—Their Occupations—Newspapers—Position of my Father’s Family—Management of the Farm—Domestic Economy—Mechanical Professions—Beef and Pork—The Thanksgiving Turkey—Bread—Fuel—Flint and Steel—Friction Matches—Prof. Silliman—Pyroligneous Acid—Maple Sugar—Rum—Dram-drinking—Tansey Bitters—Brandy— Whisky—The First “Still”—Wine—Dr. G.’s Sacramental Wine—Domestic Products—Bread and Butter—Linen and Woolen Cloth—Cotton— Flax and Wool—The Little Spinning-wheel—Sally St. John and the Rat-trap— Manufacture of Wool—Molly Gregory and Fuging Tunes—The Tanner and Hatter—The Revolving Shoemaker—Whipping the Cat—Carpets—Coverlids and Quiltings—Village Bees and Raisings—The Meetlng-House that was destroyed by Lightning—Deaconing a Hymn.

My dear C******

It will be no new suggestion to a reflecting man like yourself, that towns, as well as men, have their inner and their outer life. There is a striking difference in one respect, between the two subjects; the age of man is set at threescore years and ten, while towns seldom die. The pendulum of human life vibrates by seconds, that of towns by centuries. The history of cities, the focal points of society, may be duly chronicled even to their minutest incidents; but cities do not constitute nations; the mass of almost every country is in the smaller towns and villages. The outer life of these is vaguely jotted down

-----

p. 57

in the census, and reported in the Gazetteers; but their inner life, which comprises the condition and progress of the community at large, is seldom written. We may see glimpses of it in occasional sermons, in special biographies, in genealogical memoranda. We may take periods of fifty years, and deduce certain general inferences from statistical tables of births and deaths; but still, the living men and manners as they rise in a country town, are seldom portrayed. I am therefore tempted to give you a rapid sketch of Ridgefield and of the people—how they lived, thought, and felt, at the beginning of the present century. It will serve as an example of rustic life throughout New England, fifty years ago, and it will moreover enable me, by contrasting this state of things with what I found to exist many years after, to show the steady, though silent, and perhaps unnoted progress of society among us.

From what I have already said, you will easily imagine the prominent physical characteristics and aspect of my native town—a general mass of hills, rising up in a crescent of low mountains, and commanding a wide view on every side. The soil was naturally hard, and thickly sown with stones of every size, from the immovable rock to the pebble. The fields, at this time, were divided by rude stone walls, and the surface of most was dotted with gathered heaps of stones and rocks, thus clearing spaces for cultivation, yet leaving a large portion of

-----

p. 58

the land still encumbered with its original curse. The climate was severe, on account of the elevation of the site, yet this was perhaps fully compensated by a corresponding salubrity.